JESUS DIED TO SATISFY WRATH

AN EXHAUSTIVE ACADEMIC THEOLOGICAL DEFENSE OF SUBSTITUTIONARY ATONEMENT THEORY

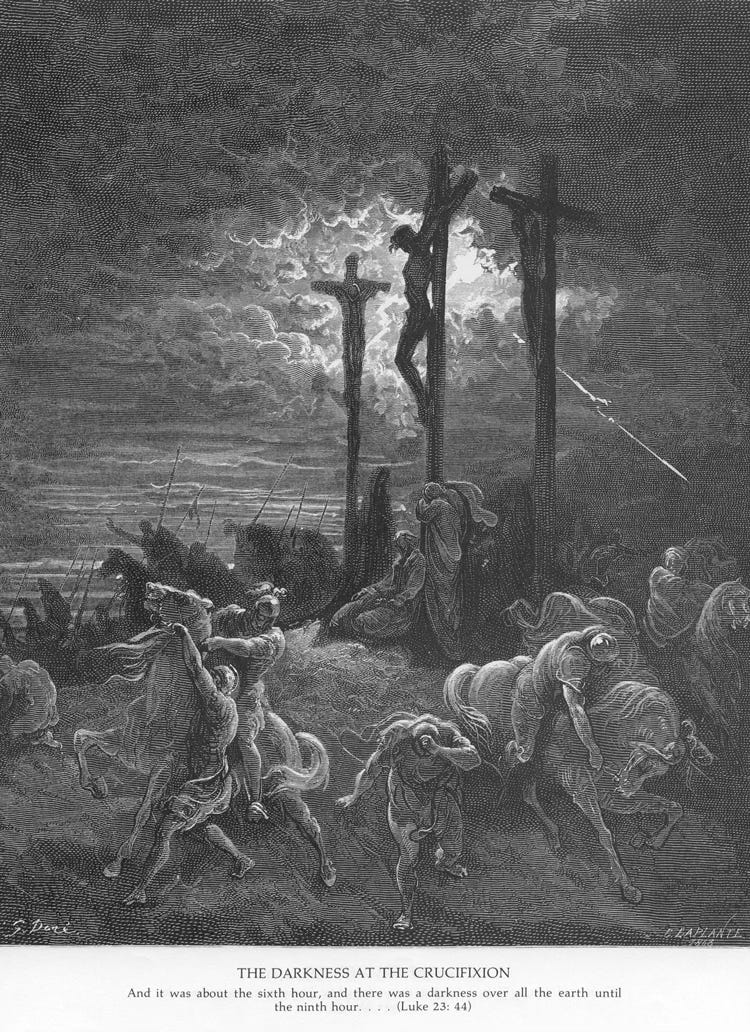

The doctrine of Penal Substitutionary Atonement (PSA) teaches that Jesus Christ, in His death on the cross, bore the penalty for our sins as our substitute. In doing so, He satisfied the justice and wrath of God on sin, allowing God to justly forgive us. For many Christians this truth is at the very heart of the gospel, “on the cross, as Jesus died, the wrath of God was satisfied,” as one popular hymn puts it. Yet in theological circles PSA has been hotly debated: some hail it as the most coherent and biblical explanation of atonement (how Christ’s death reconciles us to God), while others object to it on historical, moral, or theological grounds. In this Substack I will explore Penal Substitution in depth, explaining why it is a compelling and comprehensive atonement theory. I will also fairly present major objections raised by both historical and contemporary theologians (from the early Church Fathers to voices like N. T. Wright and Greg Boyd), and offer clear responses to those objections.

Further, I will compare PSA with alternative atonement models, including Christus Victor, Moral Influence, and the Ransom theory, showing how PSA addresses what they do, and more. An emphasis will be given to key biblical passages (such as Isaiah 53 and Romans 1–3) that support penal substitution and the reality of God’s wrath against sin.

I will trace the consistent biblical theme of substitutionary sacrifice as something that propitiates (satisfies) God’s wrath, not merely as a metaphor to appease the human conscience.

In addition, provide a comprehensive list of quotes from Church Fathers and patristic writers who support aspects of penal substitution, while also noting early Christian teachers who appeared to take different views. Those patristic differing perspectives will be addressed and reinterpreted in light of the broader theological witness.

Finally, I will discuss how the Old Testament (OT) rituals and prophecies should be read, arguing for a literal or typological understanding (as actual historical sacrifices foreshadowing Christ) rather than a purely allegorical reading that empties them of propitiatory meaning. Throughout, the aim is to be theologically rigorous yet understandable to any interested Christians.

What Is Penal Substitutionary Atonement?

Penal substitutionary atonement (often abbreviated PSA) is the idea that Christ died in our place, bearing the punishment we deserved. In other words, Jesus acted as a substitute who took the penalty (hence “penal”) for sin that we had earned, so that we, the guilty, could be forgiven and reconciled to God. One succinct definition puts it this way: “Christ’s death paid a penalty (‘penal’). As Christ did not deserve a penalty, He was paying it for others (‘substitutionary’). And the result of Christ paying this price for others is that we are now forgiven (‘atonement’).” In legal terms, God is the holy judge of all the earth who must punish evil; yet in love, God the Son willingly endures the judgment due to sinners. By this act, God’s justice is upheld even as His mercy is extended. Thus, at the cross “Jesus reconciled sinners to God by being their substitute punishment” He absorbed in His own person the righteous wrath of God against sin, so that those who trust in Him would not have to.

In PSA, God’s attributes of justice and love meet in perfect harmony. God’s justice demands that sin be punished, lest God “leave the guilty unpunished” and thus deny His own holiness and law.Yet God’s love provides the very payment He requires, by giving His own Son. Far from being a cruel Father inflicting punishment on an unwilling victim, the Bible presents this as the unified plan of a loving Triune God: the Father, Son, and Spirit together willed that the Son would become man and, out of love, offer Himself. Jesus said, “I lay down my life…No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord” (John 10:17–18). The Father “so loved the world that He gave His only Son” (John 3:16), and the Son so loved us that He “gave Himself up for us, an offering and sacrifice to God” (Ephesians 5:2). The penalty that Christ bore was our penalty,“He was pierced for our transgressions” (Isaiah 53:5). By paying it in full, Jesus could cry, “It is finished” (John 19:30), and God’s justice was fully satisfied on behalf of His people. This understanding of the cross has long been seen by evangelicals as the heart of the gospel message, indeed “the heart and soul” of how Scripture explains Christ’s saving work.

It’s important to note that PSA is not the only aspect of the atonement taught in Scripture, but it is arguably the foundational one. The early church spoke of Christ’s work using many rich metaphors (sacrifice, ransom, victory, healing, example, etc.), and modern theologians remind us not to be reductionistic. Still, penal substitution provides the underlying logic that makes the other facets possible. As one writer has put it, the cross is like white light refracted into a spectrum of colors, love, victory, justice, example, etc. and penal substitution is one “color” in that spectrum, even if not the only one. In fact, many would say it is the brightest color or the lens through which the others come into focus. I will explore those later, but first I turn to the biblical basis for Penal Substitution and why it makes sense of the scriptural testimony about the atonement.

Biblical Foundations for Penal Substitution

The doctrine of penal substitution is deeply rooted in Scripture, which consistently reveals a pattern of substitutionary sacrifice as God’s ordained means to deal with human sin. From the Old Testament sacrificial system through the prophecies of the suffering Messiah, and into the New Testament teachings of Jesus and the apostles, we see the theme: sin leads to death and judgment, but God provides an innocent substitute to bear that judgment in the sinner’s place.

Old Testament Background: Sacrifice and Substitution

From the earliest pages of Scripture, the idea of an innocent sacrifice covering the guilty is present. When Adam and Eve sinned, God clothed them with animal skins (Genesis 3:21), implying a life was taken to cover their shame. In Genesis 22, Abraham tells Isaac that “God himself will provide the lamb” for sacrifice (Genesis 22:8), and indeed God provides a ram to die instead of Isaac, a clear substitutionary act that foreshadows a Father sacrificing His beloved Son. The Passover in Egypt further cements this pattern: each Israelite family sacrificed a spotless lamb, and its blood on the doorposts turned away God’s wrath, sparing the firstborn from the plague of death (Exodus 12:12–13). The lamb died in the place of the household’s child, and God’s judgment “passed over” because a death had occurred. This was not merely about the people feeling safe; it was God’s wrath literally being averted by blood. As the New Testament later affirms, “Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Corinthians 5:7), fulfilling that type.

God wrote substitutionary sacrifice in the Levitical law given to Israel. The entire sacrificial system in the book of Leviticus is built on the concept that the wages of sin is death, but God permits a blameless animal to symbolically bear that death in the sinner’s stead. When a person sinned, they were to bring, for example, a goat or lamb “without blemish,” lay their hand on its head (identifying with it), and then kill it. The priest would “make atonement for him concerning his sin, and he shall be forgiven” (see Leviticus 4:27–31). The animal’s blood (representing its life) was given as payment for the sin. Leviticus 17:11 explains the principle: “For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it for you on the altar to make atonement for your souls; for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life.” In other words, God’s justice demands life-for-life, and He mercifully allows a substitute’s life-blood to atone. This is a penal concept (a punishment borne) and a substitutionary one. Importantly, this atonement was directed God-ward, it was about cleansing guilt before God, not just calming a person’s feelings. As theologian John Stott summarizes, in the Old Testament “it is always God who is propitiated (his wrath is turned away)… and sin which is expiated (atoned for or removed)”. The annual Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16) vividly portrayed this: one goat was slain as a sin-offering and its blood brought into the Holy of Holies to “make atonement because of the uncleanness of the people” (Lev. 16:16), and a second goat (the “scapegoat”) had the sins of the people confessed over it and was sent away into the wilderness, symbolically carrying off their sins. We see both aspects: propitiation (satisfaction of wrath by blood sacrifice) and expiation (removal of sin’s burden), achieved by substitution. The High Priest could announce that through these actions, Israel was cleansed from sin before the Lord (Lev. 16:30). The Old Covenant sacrifices were types and shadows, temporary and imperfect, needing repetition – but they pointed to a once-for-all perfect sacrifice to come (Hebrews 10:1-4). The consistent message was that sin must be paid for by blood, and God accepts a substitute in the sinner’s place.

Isaiah 53: The Suffering Servant as Substitute

Nowhere is the Old Testament expectation of penal substitution clearer than in Isaiah 53, the famous prophecy of the “Suffering Servant.” Though written hundreds of years before Christ, Isaiah 53 reads like a theological commentary on Jesus’ atoning death. It explicitly teaches that the Servant (understood by Christians to be the Messiah Jesus) would suffer the punishment due to others, in their place, to bring them peace and healing with God. Key verses include: “He was pierced for our transgressions; He was crushed for our iniquities; upon Him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with His wounds we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray… and the Lord has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isa. 53:5–6). This language unmistakably describes a substitution: the Servant is pierced and crushed not for His own sins (indeed, the passage stresses His innocence, “he had done no violence, nor was any deceit in his mouth,”), but for ours. The consequence or “chastisement” that would bring us peace (reconciliation with God) falls on Him. Verse 6 is especially vivid: all of us, the sheep, wandered into sin, but God caused the weight of our iniquity to fall on this one Lamb of God. This is exactly the logic of penal substitution: our sins are imputed to Christ, and He bears them and their penalty.

Isaiah goes on to say “it was the will of the Lord to crush Him” and to make His soul “an offering for guilt,” indicating that God Himself was involved in offering the Servant as a sacrifice (Isa. 53:10). The Servant “shall bear their iniquities” and “pour out His soul to death,” “numbered with the transgressors; yet He bore the sin of many, and makes intercession for the transgressors” (Isa. 53:11-12). Every phrase reinforces the idea of an innocent substitute bearing the sin, guilt, and punishment of the guilty. Notably, God’s will is accomplished in this suffering, it is not an accident or merely human injustice, but part of God’s redemptive plan. Some critics object that the idea of God “punishing” His Servant is divine child abuse, but Isaiah’s prophecy itself shows God’s initiative in providing this sacrifice (it was “the Lord’s will”) and at the same time the Servant’s willingness (He goes like a lamb silently to slaughter, accepting it). In Christian understanding, this finds fulfillment in Jesus, the Son of God, who willingly aligns His will with the Father’s to save us. The New Testament confirms that Jesus saw Himself in Isaiah 53, for example, He quoted Isaiah 53:12 as being fulfilled in His being “numbered with transgressors” at His crucifixion (Luke 22:37).

The early church universally interpreted Isaiah 53 as referring to Christ’s atoning death. We find strong patristic support for the penal-substitutionary reading of this text. St. Jerome (4th century), commenting on Isaiah 53, wrote: “He was put to death by God for their sins, who was humbled for us. For that which was owed to us according to our crimes, He bore it, so He suffered for us, having made peace [with God] through the blood of His cross…”. Jerome explicitly notes that Christ endured the God-ordained penalty for our sins, a clear affirmation that in Isaiah 53 God’s justice is in view (“put to death by God for our sins”) and that Christ’s blood made peace between God and us. Likewise, Athanasius in the 4th century, echoing Isaiah, declared that Jesus “suffered for us, and bore in Himself the wrath that was the penalty of our transgression”. These reflections by ancient commentators underscore that Isaiah 53 strongly teaches penal substitution , the Servant endures God’s wrath and the penalty of sin on behalf of the people, to bring us forgiveness and peace.

The New Testament: Christ Fulfills the Atoning Work

The New Testament presents Jesus Christ as the fulfillment of all those Old Testament sacrificial types and prophecies. John the Baptist identified Jesus as “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29), a title that evokes the sacrificial lambs of the OT and especially the Passover lamb. Jesus Himself said of His mission: “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45). That word ransom (Greek lytron) means a price paid to achieve the release of captives. In Greco-Roman context it was often the price to free a slave or a prisoner of war. By using this term, Jesus taught that His death would be the cost required to liberate many from bondage, bondage to sin and death. The key concept is giving His life in place of others (“for many”), which implies substitution and an underlying problem (our bondage or liability) that requires such a payment. Jesus echoed Isaiah 53’s language as well; e.g. at the Last Supper, He described the cup as “my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins (Matthew 26:28). The phrase “poured out for many” reflects Isaiah’s “he bore the sin of many” (Isa. 53:12) and signals that His imminent death is sacrificial – for the forgiveness of sins. Thus, Christ understood His own death as an atoning sacrifice that secures pardon for others.

Throughout the apostolic preaching recorded in Scripture, Christ’s death for our sins is front and center. St. Paul reminds the Corinthian church of the gospel he delivered to them: “that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4). The phrase “for our sins” ( hyper tón hamartión hemón) denotes on behalf of, or because of, our sins, a succinct statement of substitutionary purpose. Similarly, Peter writes, “Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that He might bring us to God” (1 Peter 3:18). Here again, the righteous one (Christ) suffers on behalf of the unrighteous (us), to reconcile us to God, a clear statement of penal substitution (suffering for sins) with a God-ward effect (bringing us to God). Another powerful verse is 2 Corinthians 5:21: “For our sake [God] made Him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in Him we might become the righteousness of God.” This means that on the cross, God treated Christ, who was sinless, as if He were sin itself (laden with our sin), in order that we might in exchange receive a status of righteousness before God. The great Reformers called this the “wondrous exchange” or double imputation: our sins imputed to Christ, His righteousness imputed to us. The Epistle to the Hebrews also casts Christ’s work in sacrificial terms, comparing Him to the high priest who offers a sacrifice, in this case, Himself, to take away sins “once for all” (Hebrews 7:27, 9:26). Hebrews 9:28 says “Christ was offered once to bear the sins of many,” again echoing Isaiah 53. All of these texts revolve around the idea that Jesus took responsibility for our sins and bore their consequence (death/curse) so that we might be free and counted righteous.

Romans 1–3: The Wrath of God and the Propitiation in Christ

The early chapters of Romans lay out perhaps the clearest logic for penal substitution, tying together the wrath of God, universal human sinfulness, and Christ’s atoning blood. In Romans 1:18, Paul opens the argument by declaring: “the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men.” This sets the stage: God’s just anger toward human sin is a reality, and it is “revealed”, that is, actively present, in our fallen world. In Romans 1:19–32, Paul shows how Gentiles have rebelled and are “without excuse,” incurring God’s wrath by their idolatry and immorality. In Romans 2, he turns to the moralizers and Jews who think they’ll escape judgment, warning that “because of your hard and impenitent heart you are storing up wrath for yourself on the day of wrath when God’s righteous judgment will be revealed” (Rom. 2:5). He emphasizes God’s impartial justice: “There will be tribulation and distress for every human being who does evil… For God shows no partiality” (Rom. 2:9,11). By Romans 3, his conclusion is that “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (3:23) and that every mouth is stopped, the whole world is accountable before God’s law (3:19). This is the problem: we are guilty and deserving of punishment from a holy God. The wrath of God is not capricious or spiteful; Paul describes it in terms of God’s righteous judgment (2:5), it is God’s settled, just response to evil. If the story ended here, all of us would face condemnation, for “the wages of sin is death” (Rom. 6:23).

But Paul goes on to explain the good news in Romans 3:21–26. He says that although we are unrighteous, God has now revealed a way to be justified (declared righteous) apart from our own law-keeping, “the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe” (3:22). How can this be, if God is perfectly just? The answer comes in verses 24–25: we are “justified by His grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by His blood, to be received by faith.” Several rich terms are used here: redemption (the language of ransom, Christ’s death as purchasing our release), and propitiation. The word “propitiation” (Greek hilastērion) refers to a sacrifice that satisfies God’s wrath and turns it to favor. In the Old Testament, the same term was used for the “mercy seat” on the Ark of the Covenant, where the high priest sprinkled blood to atone for Israel’s sins (Leviticus 16:15). Paul is saying that Jesus’s blood-shedding on the cross was God’s appointed hilastērion, the atoning sacrifice that absorbs divine wrath. This sacrifice is “put forward” publicly by God Himself, demonstrating His justice (Rom. 3:25b-26): “This was to show God’s righteousness… so that He might be just and the justifier of the one who has faith in Jesus.” In other words, by punishing sin in Jesus, God upholds His holy justice (He does not simply ignore sin), and at the same time He provides a way to justify sinners mercifully. God remains just, even as He justifies the unjust, because the penalty of sin has been paid on the cross. This is the crux of penal substitution: God’s law and righteousness are fully honored in Christ’s punishment, and we, through faith, receive the benefits as though we had been perfectly just. Romans 5:9 puts it plainly: “Since, therefore, we have now been justified by His blood, much more shall we be saved by Him from the wrath of God.” Our rescue from wrath is explicitly attributed to His blood (a metonym for His sacrificial death). The wrath of God that loomed over us (Rom. 1:18) has been satisfied by Jesus’ blood, so that in Him we are shielded from wrath and instead stand in grace (Rom. 5:1-2,9). The Apostle John likewise writes, “In this is love… that [God] loved us and sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins” (1 John 4:10), showing that propitiation (appeasing wrath) is an act of God’s love, not contrary to it.

All of these Scriptures, taken together, form a powerful biblical case for Penal Substitution. They show a God who is uncompromisingly just in dealing with sin, and yet who in love provides Jesus as the atoning sacrifice so that justice is fulfilled and mercy can be freely given. The holiness and wrath of God toward sin is consistently affirmed (not ignored or allegorized away), but so is God’s gracious initiative in providing the substitute. This is why many theologians consider PSA to be the most coherent atonement theory: it makes sense of why Jesus had to die (to satisfy the demands of God’s justice, which a holy God could not simply waive) and how that death achieves our reconciliation (by removing the wrath and curse due to us). As the Reformer John Calvin succinctly said: “Christ was made a substitute and a surety in the place of transgressors and even submitted as a criminal, to suffer all the punishment which would have been inflicted on them”. In the next section, we will see that this theme of substitutionary sacrifice for the satisfaction of God’s justice is not only biblical but runs consistently through the Bible’s storyline, rather than being a later invention. We will also address an important interpretive question: should we read the Old Testament sacrifices and prophecies literally, as real foreshadows of Christ’s atonement, or merely allegorically as metaphors for something else?

The Consistent Theme of Substitutionary Sacrifice (Not Allegory)

A crucial claim of Penal Substitution is that Jesus’s sacrifice actually propitiated God’s wrath, it wasn’t just a dramatic show for our subjective benefit, but it objectively accomplished something in God’s economy of justice. Some critics allege that the biblical language of sacrifice is meant to be taken allegorically or as accommodating human conscience (i.e. people felt forgiven by rituals, but God didn’t literally require a payment). Here we will argue the opposite: Scripture consistently presents substitutionary sacrifices as truly necessary to satisfy God’s righteous anger at sin. This runs from the Old Testament into the New. We will then see how the early Church largely upheld a literal understanding of these sacrifices (seeing them as real events that foreshadowed Christ’s literal atonement), as opposed to overly allegorizing them into abstraction.

First, consider again the Old Testament sacrificial system. If one were to claim this was only about calming the human conscience or symbolizing something non-literal, the biblical text itself does not support that. The Levitical laws repeatedly say that the sacrifices “make atonement” and “shall be forgiven” (e.g. Lev. 4:20, 4:26). On the Day of Atonement, it says “atonement shall be made for you to cleanse you; from all your sins you shall be clean before the Lord” (Leviticus 16:30). The phrase “before the Lord” indicates this is about our standing in God’s sight. These rituals were given by God precisely because He required atonement for sins in the covenant relationship. They were teaching Israel the gravity of sin and need for forgiveness, and they did have a ceremonial aspect , but they were not empty symbols. The New Testament book of Hebrews confirms both the efficacy and limitation of the OT sacrifices: on the one hand, they did obtain a sort of ceremonial forgiveness and foreshadowed Christ, but on the other hand, they could not ultimately take away sins or cleanse the conscience permanently (Hebrews 10:1-4). That was why they had to be repeated and why Christ’s better sacrifice was needed. Hebrews 9:13-14 contrasts the two: “the blood of goats and bulls… sanctify for the purification of the flesh, how much more will the blood of Christ… purify our conscience from dead works to serve the living God!” So the OT sacrifices were not a sham; they actually did something, but only Christ’s blood can finally cleanse the conscience and remove sin’s guilt fully. This affirms that God truly did require a sacrifice (the old ones were a figure of the true one), and Christ came to literally accomplish what animal blood could only symbolize.

Significantly, the wrath of God is directly connected with atonement in the OT. For instance, in Numbers 16, when Israel rebelled, a plague of wrath broke out and Moses tells Aaron to “make atonement for them, for wrath has gone out from the Lord” (Num. 16:46). Aaron offers incense and atonement, and the plague is stopped. This shows atonement as appeasing God’s wrath in a very concrete way. Likewise, the Passover lamb’s blood turned away God’s wrathful judgment (Exod. 12:13). These are not purely psychological; they depict God Himself responding to a substitutionary offering by relenting from wrath. The ultimate fulfillment of this pattern is Christ’s sacrifice which, as we saw, is explicitly called a propitiation (Rom. 3:25) a sacrifice that turns away wrath. The Apostle says “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us” (Galatians 3:13). Here “curse” refers to God’s curse on sinners (per Deut. 27:26); Christ bore that curse. St. John Chrysostom explained this beautifully: “As it was necessary for Him who was about to relieve from a curse [us] to be free from it, but to receive another instead of it, therefore Christ took upon Him such [a curse], and thereby relieved us from the curse. It was like an innocent man’s undertaking to die for a criminal sentenced to death, and so rescuing him from punishment. For Christ took upon Him not the curse of His own transgression, but the curse of others, in order to remove it from them.”newadvent.org. This 4th-century father’s analogy underscores that Christ’s taking the curse for us was literal and effective. It actually removed the curse/punishment from us. This was not an allegory for a mere change in our psyche; it was a legal and relational transaction before God. Thus, biblically, the idea that sacrifices and Christ’s death only mattered for human subjective understanding falls flat. The consistent scriptural theme is God demanding justice and God providing the substitute sacrifice to satisfy that justice.

Allegory vs. Typology: Patristic Interpretation of Rituals

The early Christian Church generally understood the Old Testament sacrifices and prophecies in a literal way that is, they saw the OT institutions as real God-given foreshadows of Christ’s work, not as meaningless rituals to be allegorized away. Typology recognizes that events or persons in the OT (the “type”) genuinely prefigure a greater fulfillment in Christ (the “antitype”), while still affirming the historical reality and God-intended purpose of the original event. Allegory, in contrast, often sought hidden spiritual meanings divorced from the literal sense. Some church fathers , especially of the Alexandrian school like Origen, did employ allegorical interpretation heavily. Origen, for example, might read the animal sacrifices as symbols of virtues or of spiritual self-denial, etc., beyond their literal sense. However, even Origen acknowledged the Christological foreshadowing in many cases (he saw the Passover lamb, for instance, as a figure of Christ, and Isaac’s near-sacrifice as prefiguring. The danger was that extreme allegory could explain away the plain meaning something that more “literalist” fathers cautioned against.

Notably, the Antiochene school of interpretation, including Theodore of Mopsuestia, Diodore of Tarsus, John Chrysostom, and others, strongly resisted over-allegorizing. Theodore of Mopsuestia rebuked those who “make everything in the scriptures serve their own ends. They dream up silly fables in their own heads and give their folly the name of allegory.” Instead, he and the Antiochene tradition emphasized the historical meaning and the genuine prophetic significance intended by the text itself. For instance, when Isaiah 53 describes a servant bearing sins, that was taken as a direct prophecy of Christ’s atonement, not just a metaphor for, say, the nation of Israel or a generic idea of suffering. The Church Fathers overwhelmingly saw passages like the Passover, the Day of Atonement, the sacrificial lambs, etc., as literal events ordained by God which at the same time foreshadowed Christ’s literal sacrifice. Justin Martyr in the 2nd century, in his Dialogue with Trypho, speaks of many OT types of Christ’s cross (the Passover lamb, the bronze serpent lifted up, etc.), arguing they were providential pointers to the real salvation accomplished by Jesus. St. Irenaeus (late 2nd century) insisted that “all the prophets have announced Christ” and that types like the ram offered by Abraham instead of Isaac clearly prefigured the Son of God’s sacrifices. These fathers did not think God’s commands for sacrifice were arbitrary; rather, “all things which have been given by God from the beginning of the world, unto man, are the typifying of Christ” as one early Christian citation (2 Nephi 11:4) echoed In the patristic view, the “red line” of sacrificial blood runs through Scripture bearing witness to the need for the Messiah’s blood. The reality of blood sacrifice was never denied indeed, the early Christians taught that the era of animal sacrifices ended precisely because the real sacrifice had come, rendering the “copies” obsolete.

Even those known for allegory, like Origen, accepted that Jewish sacrifices “foreshadowed the sacrifice of Christ”, urging careful interpretation to discern their typological meaning, The difference is that Origen might multiply layers of meaning (moral, spiritual allegories) beyond the straightforward typology. But importantly, no major Church Father taught that God did not actually require or accept Christ’s sacrifice. On the contrary, they emphasize its necessity and efficacy. For example, St. Cyril of Jerusalem (4th century) in his Lectures speaks of Christ as the true sacrificial Lamb whose blood saves, directly paralleling and fulfilling the OT lamb. St. John of Damascus (8th century) sums up earlier tradition by listing numerous OT types of the Cross (the tree of life, Jacob’s crossed hands, the bronze serpent, etc.) and says: “the tree of the cross brought salvation…just as Christ was nailed to the tree in the flesh”. This shows they read those OT stories as intentional signs of literal events in Christ’s passion (not just symbols of abstract truths).

In short, the mainstream patristic approach was realistic and Christ-centered: the Old Testament rituals and prophecies were trustworthy revelations that found literal fulfillment in Jesus’s atoning death and resurrection.

They often criticized excessive allegorism that ignored the factual meaning of Scripture. Eustathius of Antioch (4th cent.) directly challenged Origen’s allegory of the Witch of Endor story, arguing one must respect the integrity of the text

Diodore of Tarsus wrote, “we prefer much more the historical comprehension of the text than the allegorical”. indicating the value placed on what actually happened and what was concretely prophesied. This lends support to our argument: the early church by and large believed that the Old Testament sacrificial imagery was meant to foreshadow Christ’s actual sacrifice for sin, which did in reality appease God’s wrath and procure forgiveness. Thus, penal substitution is not a product of misreading the Bible literally, it is, in fact, the result of reading the Bible the way the prophets and apostles intended, as testifying to a real atoning sacrifice ordained by God.

Comparing Atonement Theories: Christus Victor, Moral Influence, Ransom, etc.

Christ’s death on the cross is so rich in significance that over the centuries, Christians have described it using different theories. Aside from Penal Substitution, three classic models often discussed are Christus Victor, Moral Influence, and the Ransom Theory. Rather than mutually exclusive theories, these can be seen as complementary facets, yet some theologians have advocated one to the exclusion of others. Here we will briefly explain each and show how Penal Substitution relates to or undergirds them.

Christus Victor (Christ the Victor): This view emphasizes the cross as Christ’s victory over the powers of evil, Satan, sin, and death. The term comes from Gustav Aulén’s analysis of the “classic” view of the atonement in the early church, According to Christus Victor, humanity was in bondage to forces (the devil, demonic powers, death itself), and Jesus defeated these powers through His death and resurrection, thus liberating us. Indeed, the New Testament does present the cross and resurrection as a conquest: “He disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, triumphing over them in the cross” (Colossians 2:15). Hebrews 2:14 says Christ became human “that through death He might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil.” Christus Victor captures the dramatic cosmic victory aspect of the atonement. How does this relate to Penal Substitution? In truth, PSA and Christus Victor are not at odds, they address different dimensions of what Jesus achieved. PSA focuses on how the cross deals with our guilt before God (the legal problem), whereas Christus Victor focuses on how it delivers us from our enemies (the existential problem). The Bible holds both together. For example, immediately after saying Christ bore our sins (penal substitution), Isaiah 53 also says “He shall divide the spoil with the strong” (Isa 53:12), implying a victory and reward. By satisfying God’s justice, Jesus broke the legal claim that Satan had over us (our guilt). Once sin’s debt is paid and God’s wrath appeased, the devil is disarmed, he can no longer lawfully accuse us (cf. Rom. 8:33-34). Thus, Christ’s victory is grounded in the substitutionary atonement. As N. T. Wright has remarked, it’s unwise to pit Christus Victor against PSA: the New Testament sees the cross as both the place where “God condemned sin in the flesh” (legal) and where Jesus “defeated the powers” (victory), Wright argues we shouldn’t separate the two, because by bearing sin’s penalty, Jesus robbed the powers of their ammunition. In practical terms, believers can joyfully affirm both “Thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor. 15:57) a victory made possible because “Christ died for our sins” (1 Cor. 15:3).

Moral Influence (or Example): This view (associated historically with Peter Abelard in the 12th century) sees the primary effect of the cross as a demonstration of God’s love that softens human hearts and inspires us to repentance and love for God in return. According to the Moral Influence theory, the problem is not that God’s wrath needs satisfaction, but that we are estranged in our attitude, we distrust or hate God, and the cross shows how much God loves us (since He would even suffer and die for us), thereby moving us to love Him. Certainly, the cross does powerfully reveal God’s love, Scripture says “God shows His love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Rom. 5:8). The self-sacrificial love of Christ, praying “Father forgive them” for His executioners, is the ultimate moral example and has indeed transformed millions of lives. However, taken alone, the Moral Influence theory doesn’t explain the necessity of the cross. If the cross were only a demonstration, one might ask: was such a terrible death needed merely to prove a point? Could God not show love in some less extreme way? The moral influence view tends to downplay the objective problem of guilt and God’s justice. Penal substitution, by contrast, provides the essential backdrop that amplifies the love on display. When we understand that on the cross Jesus was doing more than showing love, that He was actually taking our law-place under God’s judgment, then the love is seen to be far more than sentiment; it’s love in action, love that cost something. As one theologian famously said, “God’s love found a way to satisfy God’s justice.” PSA teaches that Christ’s death had God-ward efficacy (propitiating wrath), not just man-ward influence. Yet it does also have man-ward influence: when we grasp that “He loved me and gave Himself for me” (Gal. 2:20), it compels us to love (1 John 4:10-11). Thus, Penal Substitution includes the Moral Influence effect as a fruit of the atonement, but not its whole rationale. By dealing with sin’s penalty, Jesus actually removes the barrier that kept us from experiencing God’s love fully. Abelard’s concern was to correct crude views of the cross as a transaction divorced from love; ironically, PSA properly understood is the ultimate proof of love, because the Father and Son went to such lengths to save us, In summary, the Moral Influence theory captures an important truth, the cross changes our hearts but it cannot stand alone. Without PSA, the cross’s display of love becomes hollow, because it fails to explain what that love achieved.

Ransom Theory: This is one of the oldest concepts, the idea that Christ’s death was a ransom price paid to secure our freedom. It’s a biblical concept (Jesus said His life is a ransom for many, Mark 10:45), but who is the ransom paid to? One stream of early Christian thought, originating with theologians like Origen, imagined that the ransom was paid to the devil, because humans, by sinning, had effectively sold themselves under the devil’s dominion. According to this scenario, the devil claimed rights over humanity, so God offered His Son as a ransom exchange. The devil, thinking he would gain power over Jesus, agreed; but because Jesus was sinless, death could not hold Him, He rose, and the “bait” of Christ’s human flesh hid the “hook” of His divinity that hooked the devil and defeated him. This narrative is known as the Ransom-to-Satan theory. Gregory of Nyssa (4th cent.) was a chief leader of a refined version of this: he describes the devil as a “ravenous fish” and Christ’s divinity as the hook hidden by the bait of His humanity. In being tricked into overreaching, trying to consume a sinless soul, Satan effectively self-destructed and lost his captives. The theory highlights God’s wisdom in outsmarting the devil and the triumph of Christ over the powers. However, it raises problems: it can exaggerate Satan’s rights owing him nothing, God could defeat him without “paying” him, and it sidelines God’s righteousness.

In hindsight, theologians see the “ransom to Satan” language as a metaphor, the cross did secure our release from Satan’s bondage, but not by reimbursing the devil, rather by satisfying God’s justice, thus nullifying Satan’s accusation rights, and by tricking the devil in a figurative sense, Satan did not foresee that killing the Messiah would actually lead to his own defeat. The more theologically precise way to frame “ransom” is that Christ’s life was the ransom paid to God’s justice the debt of honor or punishment we owed to God.

This was essentially St. Anselm’s view in the 11th century, he shifted the target of the payment from Satan to God’s honor/justice, laying groundwork for PSA. Even Scripture suggests God is the one ultimately owed: “Christ gave Himself as a ransom to God”1 Timothy 2:6. Therefore, Penal Substitution fulfills the true meaning of the Ransom: Jesus said He came to give His life as a ransom for many, the Greek preposition anti means in place of , indicating substitution. By dying in our place, He frees us from slavery, slavery to sin, death, and the devil. The devil’s “right” to accuse us was based on our guilt; once the guilt is gone (paid for), his power is broken. Thus, PSA actually explains how the ransom works and connects it with God’s justice, avoiding the pitfall of portraying God as bargaining with Satan.

To summarize the comparison: Christus Victor emphasizes the triumph of the cross, Moral Influence emphasizes the love displayed, and Ransom emphasizes the cost paid to deliver us. Penal Substitution, rather than being a competing theory, provides a framework in which these elements cohere. In PSA, the cross is a victory, but a victory achieved by satisfying the law’s penalty that stood against us (Col. 2:14-15). It certainly is the supreme demonstration of love, but a love that is not merely exemplary, actually effective in removing our sin. And it is a ransom, the precious blood of Christ is the price of our redemption (1 Peter 1:18-19), offered to God to redeem us for Himself. The various biblical metaphors of atonement (legal justification, sacrificial cultus, warfare and victory, slavery and ransom, moral example, healing, adoption, etc.) are all true in their own way. The richness of Christ’s work cannot be reduced to one image. However, as an atonement theory, penal substitution has a unique explanatory power because it goes to the heart of the issue: our objective guilt before God. Without addressing that, none of the other benefits (defeating Satan, transforming our hearts, etc.) would resolve our standing before a holy God. This is why many theologians across traditions consider penal substitution or its close cousin, satisfaction, as the foundational layer of the atonement, with the other aspects being built upon.

Historically, the Eastern Orthodox church emphasized themes of victory, deification, and resurrection; medieval Western theology (Anselm) emphasized satisfaction of God’s honor/justice; Reformers sharpened that to penal substitution justice in terms of legal penalty. Modern theologians often seek a holistic approach that incorporates all. N. T. Wright, for instance, argues that we shouldn’t create false dichotomies: “We must insist that Christus Victor and penal substitution are not an either-or” the full biblical picture needs both. We can joyfully affirm that on the cross, Jesus both conquered our foes and atoned for our sins.

Objections to Penal Substitution and Responses

Penal substitution, though deeply grounded in Scripture, has faced several critiques. It’s important to engage these concerns directly, as they often arise in discussions with both believers and skeptics. lets outline major objections, from the charge of “divine child abuse” to claims that PSA was absent in the early church, and provide responses to each:

Objection 1: “Penal substitution is divine child abuse” (God punishing an innocent Son is unjust and unloving). This emotive charge was popularized by critic Steve Chalke who called PSA a form of “cosmic child abuse.” Similarly, theologian Greg Boyd and others argue that PSA portrays God as a wrathful monster who must inflict violence on His Son, seemingly at odds with Jesus’s message of mercy. Response: This objection rests on a caricature. PSA does not teach that the Father sadistically punished an unwilling Son. Rather, it insists that Father, Son, and Spirit willingly collaborated from eternity in the plan of redemption, often called the covenant of redemption. The Son of God voluntarily assumed human nature and offered Himself. As Jesus said, “No one takes my life from me, but I lay it down of my own accord” (John 10:18). Thus, the cross is an act of self-sacrifice by God. The Father’s role was not that of a cruel tyrant venting rage on a third party, but of a judge who out of love “did not spare His own Son but gave Him up for us all” (Rom. 8:32). The Son’s role was to lovingly agree to bear our sin. Isaiah 53 beautifully balances these: “it was the will of the Lord to crush Him… when His soul makes an offering for guilt” , God willed it, yet in the same passage, “He, the Servant, poured out His soul to death”, indicating volition. Importantly, Jesus is not a child in the sense of a separate human person being coerced, He is Himself fully God, one with the Father (John 10:30). So, God Himself absorbed the punishment. Far from being unjust, this was the greatest act of justice and mercy combined: justice, because sin was duly punished (not swept under the rug), and mercy, because God took that punishment on Himself. Legally speaking, one might ask, “How can an innocent man be punished for the guilty, isn’t that unjust?” The gospel answer is that Jesus was our representative head (the Second Adam). Just as we fell in Adam (who represented humanity), so Christ represents a new humanity. By union with Him, our guilt becomes His and His righteousness ours (2 Cor. 5:21). Because He willingly stands in our stead, there is no injustice, it’s akin to someone volunteering to pay another’s debt. Even human law allows substitution in penalties if the one with the penalty consents, a debt or a fine can be paid by another. With capital punishment it’s not possible among humans, but Jesus’s unique identity (fully human and fully divine) allowed Him to be the covenant head and substitute for millions. It’s also critical to highlight the love of the Father in PSA: It was God’s love that sent Christ to the cross (John 3:16, 1 John 4:10). The Father was not reluctant or angry at the Son; rather, “God was in Christ reconciling the world to Himself” (2 Cor. 5:19). The Father’s wrath is against sin, but in love He provides the Lamb. As theologian J.I. Packer said, the Father’s wrath is “born of holiness; the Son’s absorbing of that wrath is born of love”, no conflict in God’s heart. Even N. T. Wright, who is cautious about caricatures, affirms: “It is not the case that an angry Father forces punishment on an innocent Son. Jesus himself... chose the path of the cross… The triune God, in the person of the Son, absorbs the consequences of our sin”. The cross, then, is God-substituting-Himself for us, not God abusing someone else. With this understanding, the charge of “child abuse” completely misses the mark – the cross was the supreme act of love and agreement within the Godhead for the sake of our salvation.

Objection 2: “If God forgives, He should just forgive, requiring blood sounds primitive and unworthy.” Some argue that true forgiveness means letting go of the offense without payment. Critics from liberal theology or other religions sometimes say: why can’t God just declare forgiveness mercifully? Why the need for a violent sacrifice? Isn’t that more akin to pagan gods who demand appeasement? Response: God’s forgiveness in Scripture is always free to the sinner, but costly to the forgiver. The holiness and justice of God mean that He cannot simply ignore sin without ceasing to be righteous. Exodus 34:6-7 describes God as merciful and forgiving, yet “who will by no means clear the guilty”, a tension resolved only at the cross. Consider even on a human level: if someone deeply wrongs you, and you choose to forgive, you bear a cost, absorbing the pain instead of retaliating. You “pay” the debt internally so the other is freed from it. Likewise, God in forgiving us doesn’t wave a magic wand; He bears the cost in Christ. The cross was God’s way of righteously dealing with sin’s debt. Hebrews 9:22 notes, “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness”, not because God is bloodthirsty, but because blood represents life given in substitution, it satisfies the lawful consequence of sin (death). Additionally, God is a God of justice (Psalm 89:14 says righteousness and justice are the foundation of His throne). If a human judge just acquitted murderers out of “mercy,” we’d call that corruption. How much more must the Judge of all the earth “do right” (Genesis 18:25)! The genius of the gospel is that God found a way to punish the sin while pardoning the sinner, by punishing it in Himself. Far from unjust, Romans 3:26 emphasizes that the cross was to “show God’s righteousness… so that He might be just and the justifier of the one who has faith in Jesus.” Moreover, the idea of sacrifice for atonement was instituted by God Himself, not borrowed from pagans. Pagan sacrifices are distortions; in the Bible, it is ultimately God providing the sacrifice to satisfy His own justice (as with Abraham: “God will provide for Himself the lamb,” Gen. 22:8). This underscores that grace is not cheap, forgiveness is free to us, but costly to God. A God who simply shrugged off evil without any payment would not be holy or trustworthy; but the God of the Bible is both “just and merciful.” The cross upholds moral order (sin is condemned) even as it saves the offender. As Anselm answered long ago: “You have not yet considered how heavy the weight of sin is.” If we grasp God’s infinite purity, we understand why atonement is necessary. Finally, the resurrection shows God’s approval of Christ’s payment, having paid in full, Christ is raised victorious, proving that the sacrifice was sufficient and that forgiveness is now righteously given.

Objection 3: “Penal substitution was not the dominant view in the early church; it’s a later (Reformation or medieval) development, so it lacks historic pedigree.” This argument is often raised by Eastern Orthodox theologians and some modern scholars. They point out that early Church Fathers spoke more in terms of ransom, victory, or recapitulation, and that a fully fleshed “penal substitution” theory is found explicitly in the West (Anselm, Calvin). The claim is that PSA is absent in the first 1000 years of Christianity, thus it might be a theological innovation.

Response: It is true that the early church did not use the later technical language of “penal substitution”, but like the other theories presented, the core concepts of Christ suffering in our place, bearing our penalty, to appease God’s wrath are indeed present from the beginning. We have already cited many biblical and patristic examples. For instance, around A.D. 200 (well before medieval times), the Epistle to Diognetus rejoiced in the “sweet exchange” by which Christ, the righteous, took on the sins of the lawless and imparted His righteousness to them. It asks, “In whom was it possible for us, the lawless and ungodly, to be justified, except in the Son of God alone?... O sweet exchange! O the incomprehensible work of God, that the sinfulness of many should be hidden in One righteous person, while the righteousness of One should justify many sinners!”

This clearly portrays substitution and even what we’d call imputation.

Eusebius of Caesarea (early 4th cent.) explicitly connects atonement with penalty: “Christ, being apart from all sin, received the sins of men on Himself, and therefore He suffered the penalty of sinners, and was pained on their behalf”.

He even says Christ “discharged the debt” on our behalf.

We’ve already noted Athanasius taught that Christ “bore in Himself the wrath that was the penalty of our transgression”

St. Augustine in the 5th century wrote, “He who was without sin took our punishment, that we might be delivered from punishment” (Contra Faustum, XIV.4, paraphrase).

St. John Chrysostom likened Christ to an innocent man who dies for a criminal so the criminal can go freenewadvent.org.

Hilary of Poitiers called Jesus “a victim to God the Father” offered for us.

These quotes show that, while a “penal substitution theory” systematic presentation may not have been the main focus in all their writings, the essential elements, sin as deserving punishment, Christ as sinless, Christ suffering the punishment in our place by the Father’s plan, were taught.

Some scholars (e.g. Gustaf Aulén) perhaps overstated the exclusion of PSA in the early church. More recent studies have demonstrated a balance: the Fathers employed a mosaic of atonement images. They did heavily emphasize victory over Satan and death (understandable in their context), but did not deny substitution. We must remember, doctrine often develops in clarity over time. The Reformers in the 16th century made PSA more central and explicit, but they would argue, that they were systematizing biblical truths that were always there. Additionally, the Eastern Orthodox ,who are often critical of PSA, still affirm that Christ’s death was an atoning sacrifice. They might articulate it in terms of Christ’s voluntary self-offering to cleanse sin rather than legal penalty, but even Orthodox liturgy calls Jesus “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world”, language directly from Scripture. Some Orthodox voices today acknowledge that a balance is needed: for example, Orthodox writer Georges Florovsky wrote that the early church did know the idea of expiation and propitiation, not just victory. It’s also worth noting that even if a doctrine’s full explanation came later, that doesn’t make it untrue, the Trinity wasn’t fully defined in creeds until the 4th century, yet it’s implicitly in Scripture. Likewise, PSA is woven into the biblical text, and glimpsed by the Fathers, even if “Christus Victor” was their banner headline. In fact, as shown above, more than a few Fathers explicitly expressed penal-substitutionary ideas. The claim that “no one believed this for 1500 years” is overstated. The Council of Trent in 16th cent. (Catholic) and the Reformation confessions (Protestant) both affirmed Christ’s death propitiated God, but understanding “satisfaction” slightly differently. The theological term “penal substitution” may be later, but the apostolic teaching of Christ dying for our sins to reconcile us to God is as old as the New Testament. Therefore, PSA stands on solid historic Christian ground when properly understood as part of atonement teaching throughout the ages.Objection 4: “Emphasizing God’s wrath and appeasement makes God seem angry all the time, undermining His love and the primacy of grace.” Some worry that PSA shows the image of God, making it sound like God the Father needed to be satisfied or that He doesn’t actually love humanity until Jesus convinces Him by dying. They prefer to stress God’s love and mercy. Response: The Bible reveals God’s wrath and love in harmony. “God is love” (1 John 4:8), indeed, and that is why He is wrathful against sin, because sin destroys His beloved creatures and is antithetical to His goodness. Wrath in God is not a bad temper or malice; it is His holy reaction to evil. It exists alongside His compassion. In Exodus 34, God describes Himself as abounding in love and by no means clearing the guilty. The Psalms say, “He has indignation every day” at the wicked (Ps. 7:11) but also that “His anger is but for a moment, and His favor is for a lifetime” (Ps. 30:5). The cross showcases both aspects: God’s love initiated the remedy for His own wrath. Romans 5:8-9 wonderfully balances this: “God shows His love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. Therefore we have now been justified by His blood, much more shall we be saved by Him from the wrath of God.” Here, the motive is love, the means is blood, the result is saved from wrath. Far from undermining grace, PSA highlights grace, because we see what it cost God to save us. If there were no wrath, grace would be cheap (what exactly are we saved from?). By fully acknowledging wrath, we appreciate grace all the more: we deserved wrath, we got favor instead, at Christ’s expense. Moreover, the Son’s work wasn’t to change the Father’s disposition from hate to love; rather it was the expression of the Father’s love. Think of it this way: the Father’s love provided what His holiness required. The Father himself “so loved the world that He gave His Son” (John 3:16). Sometimes critics set up a false dichotomy: an “angry OT God” vs “loving NT Jesus.” But biblically, the same God who is angry at sin is the one who out of love sent Jesus (and indeed it’s Jesus who speaks of hell and judgment quite often!). On the cross, God’s love and wrath meet: “Mercy and truth have met together; righteousness and peace have kissed” (Psalm 85:10). A God without wrath who tolerates evil and forgives without justice would not be truly righteous or worthy of worship, and a God without love would leave us hopeless. Thankfully, the true God is both infinitely just and infinitely loving. PSA doesn’t pit Father against Son (as long as it’s taught correctly); rather, it shows the triune God’s united front against sin and for our salvation. Finally, recall that propitiation and expiation are two sides of atonement, God’s wrath is propitiated (turned away) and our sins are expiated (removed). The result is reconciliation and adoption: we who were once “children of wrath” (Eph. 2:3) become beloved children of God. The emphasis on wrath is not end of story; it’s the dark backdrop that makes the grace shine. As P. T. Forsyth said, “Unless there is something in God which the atonement satisfies, the atonement is not a reality but an appearance.” Thankfully, Christ’s atonement does satisfy the real requirement of God’s holiness, and this in no way diminishes God’s love, it demonstrates it (Rom. 5:8).

Objection 5: “Penal substitution is too legalistic or based on Western courtroom imagery, which might not resonate with other cultures or with the more mystical Eastern Christian idea of salvation as healing and theosis (union with God).” In Eastern Orthodoxy, salvation is often spoken of as therapeutic: Christ became man to heal our corrupted nature, to conquer death, and to make us “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4). Critics might say PSA’s focus on guilt, law, and punishment is a Western juridical lens that neglects the relational, participatory aspect of salvation. Response: Law-court imagery is indeed one biblical metaphor, but not the only one. PSA doesn’t deny the transformative aspects of salvation, it actually can ground them. If we ask, how can we be united to God (who is holy) or filled with His life if we remain guilty and under judgment? The legal removal of guilt is a prerequisite for the relational restoration and indwelling of the Spirit. Justification (forensic) and regeneration, sanctification (transformative) are complementary. The Orthodox emphasis on theosis (union with God) is beautiful, and nothing about PSA opposes it; rather, by destroying the barrier of sin, Jesus’s work enables us to be reconciled and filled with God’s presence (Romans 5:1-5, we have peace with God and His love poured into our hearts by the Spirit). In fact, even Orthodox theology, though it doesn’t use the term penal substitution, acknowledges Christ as sacrifice. The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom refers to Jesus as “Thine only-begotten Son... Who gave Himself up for the life of the world,” language of offering. Orthodox bishop Kallistos Ware wrote, “Orthodox don’t see the Cross as the Father punishing the Son – but we do see it as a sacrifice offered to God in love.” So the concept of sacrifice to God is there; Orthodoxy’s difference is more about the tone. We can appreciate different emphases, but ultimately, the New Testament itself uses legal terms (justified, law, curse, debt) and familial terms (reconciliation, adoption) and medicinal terms (healing) to describe salvation. They are different facets of the diamond. In Scripture, the Apostle Paul can move from legal imagery (justification) to accounting imagery (“not counting their trespasses against them”, 2 Cor 5:19) to adoption imagery (Gal. 4:5) fluidly. Therefore, PSA need not be seen as reducing the richness; it addresses the foundational forensic issue that then opens the door to relational restoration (knowing God as Father) and ontological change (new birth, sanctification, eventually glorification). The legal and the relational are linked: in human terms, an estranged relationship often needs wrongs to be acknowledged and justice done (or debt forgiven) before reconciliation occurs. Likewise, God as righteous judge forgives us justly through the cross, so that God as loving Father can embrace us prodigals without compromising holiness. So while language of “satisfaction, law, penalty” might sound dry to some, it serves the very warm goal of a healed relationship and union with God. One might say penal substitution is the mechanism by which the great Physician heals our souls, He had to remove the poison of guilt and the sentence of death to give us new life. In conclusion, PSA is not at odds with seeing salvation as healing or victory or union; it undergirds those other aspects by first solving the divine-human estrangement (caused by sin) in a definitive way.

We have addressed the most common objections: the “unjust/child abuse” accusation answered by Trinitarian unity and Christ’s willing love, the concern about forgiveness requiring punishment, answered by God’s holy justice and the concept of costly grace, the historical claim, answered by patristic evidence of substitution concepts, the wrath vs love tension, answered by understanding their harmony, and the legalism concern answered by integration of legal and relational motifs. Through all these, Penal Substitution emerges still as a thoroughly biblical, morally coherent, and pastorally powerful doctrine. Properly taught, it magnifies God’s love, since God Himself provides and becomes the sacrifice, it upholds God’s justice, evil is not ignored, and it gives assurance to believers, since our debt was truly paid, we don’t live in fear of condemnation, “there is now no condemnation for those in Christ Jesus,” Rom. 8:1).

Patristic Witness in Support of Penal Substitution

To further solidify that Penal Substitution is not an alien imposition on Christian theology, this section provides a list of quotes from early Church Fathers and other patristic sources that resonate with PSA themes. These quotations show that the idea of Christ dying as our substitute, bearing the penalty for our sins and propitiating God, can be found (at least in seed form) throughout church history:

Clement of Rome (1st century): “Because of the love that He had for us, Jesus Christ our Lord, in accordance with God’s will, gave His blood for us, and His flesh for our flesh, and His life for our lives.” (1 Clement 49:6) – Here Clement describes Christ’s death as an exchange of life for life, indicating substitutionThis is a general substitution reference; Clement emphasizes love, and while he doesn’t mention wrath, the notion of life for life is present.

The Epistle to Diognetus (c. 2nd century): “God gave His own Son as a ransom for us – the Holy One for the lawless, the Innocent for the guilty, the Just for the unjust… O sweet exchange! … that the sinfulness of many should be hidden in One righteous man, and the righteousness of One justify many sinners!”

This passage explicitly celebrates the substitution, Christ the innocent in place of us the guilty, and even alludes to double imputation, our sin to Him, His righteousness to us. It’s perhaps the clearest early Christian statement of penal substitution, calling it an “exchange” initiated by God’s mercy.Eusebius of Caesarea (early 4th century): “Christ, being apart from all sin, received the sins of men on Himself. And therefore He suffered the penalty of sinners, and was pained on their behalf; and not on His own.”

Eusebius plainly states that Christ took our sins and their penalty despite being sinless. He further writes that as our High Priest Christ “laid down His life as a ransom for the many” and “paid the debt by His death”. This is strong patristic evidence of a penalty-bearing substitution.Athanasius of Alexandria (4th century): “He did not die as being Himself liable to death: He suffered for us, and bore in Himself the wrath that was the penalty of our transgression.” (Letter to Marcellinus, interpreting Psalm 88: “Thou hast made Thy wrath to rest upon me… I paid that which I never took.”)

Athanasius elsewhere in On the Incarnation explains that humanity was under the debt of death due to sin, and Christ by His death met that obligation on our behalf, so that God’s law might be satisfied and we delivered. Here in the letter, he explicitly mentions Christ bearing God’s wrath as the penalty, a direct penal substitution affirmation.Hilary of Poitiers (4th century): He describes the Son as “a victim to God the Father” in our place. Also in his Homily on Psalm 53, Hilary says: “the Son of God… offered Himself to the wrath of the Father in order that He might appease it” . This shows a Western father acknowledging the propitiatory aspect of the sacrifice, Christ as a victim offered to God.

John Chrysostom (4th century): “It was like an innocent man’s undertaking to die for a criminal sentenced to death, and so rescuing him from punishment. For Christ took upon Him not the curse of His own transgression, but the curse of others, in order to remove it from them.” (Commentary on Galatians 3:13)

Chrysostom, the great preacher of Antioch and Constantinople, here explains Galatians, that Christ becoming a curse for us is analogous to an innocent one dying instead of the guilty to free them. He emphasizes the exchange of curses: we had the curse of law-breaking; Christ, being curse-free, took another’s curse (ours) to free us.Augustine of Hippo (5th century): Augustine frequently speaks of Christ’s death as the sacrifice for our sins, satisfying the claims of God’s justice. In Contra Faustum (XIV.10) he says, “Jesus Christ… took upon Himself the punishment due to our sins, which we deserved, and suffered for us, and made satisfaction to the Father.” Also, “By His blood He absolved the sentence of death” (Sermon 231). In another work he writes, “He who is without sin, was made sin and was made a curse (for us)… with the penalty that we had deserved, He was punished for us”

Augustine’s teaching strongly upholds that God’s justice demanded a penalty, Christ endured it, and thus God can be merciful to us.Cyril of Alexandria (5th century): In commenting on John 19:30 (“It is finished”), Cyril wrote that Christ “paid for us a debt which He did not owe” and that by His death He “appeased the Father” on our behalf (Glaphyra on the Pentateuch). Cyril taught that Christ’s death was a sacrifice that truly turned away God’s wrath from us, calling Christ the “propitiation for our sins” based on 1 John 2:2.

The Liturgies and Creeds: Early Christian worship texts also reflect substitutionary atonement. The Nicene Creed (325/381) says Jesus “for us men and for our salvation came down… was crucified for us.” The phrase “for us” (hyper hemōn) means on our behalf, implying in our place. The Liturgy of St. Basil (4th cent.) addresses Christ: “Thou hast given Thyself as a ransom to death in which we were held, sold under sin… And having descended into Hades through the Cross… Thou didst make an end of all enmity.”

In other words, Penal Substitution has deep roots in the thinking and teaching of the early Church.

Conclusion: Satisfied Wrath and Saving Grace, The Glory of Penal Substitution

We have journeyed through Scripture, theology, and church history to examine Penal Substitutionary Atonement, and we find it to be a doctrine that magnificently upholds both the holiness and love of God. Far from being an outdated or barbaric notion, penal substitution reveals the wisdom of God’s plan: He Himself provides the acceptable sacrifice to meet the demands of His justice, so that in Christ, God is both just and the justifier of those who have faith (Rom. 3:26).

Key biblical passages like Isaiah 53 and Romans 1–3 leave little doubt that the Messiah’s suffering was on behalf of others and propitiatory (turning away God’s wrath). One would need to run to translation errors (denied by original Hebrew language and ancient manuscripts) to avoid these.

Isaiah foretold a Savior who would be “pierced for our transgressions” and bear the iniquities of the many, and the New Testament presents Jesus as precisely that sin-bearing, curse-bearing Lamb of God. Paul’s Gospel of justification by faith is incomprehensible without the cross as a satisfaction of divine justice – God set forth Christ Jesus as a propitiation “by His blood” to demonstrate His righteousness, such that He can righteously declare sinners righteous. This is why penal substitution is often called the heart of the atonement: because it addresses the root issue, our legal guilt and liability before God, and thus opens the door to every other blessing , reconciliation, new life, victory over evil.

Throughout this paper, we clarified misunderstandings: PSA does not pit the Father against the Son, nor reduce God to pure wrath or the Son to a passive victim. Instead, it shows the unity of purpose in the Trinity: the Father’s love sending the Son, the Son’s love freely offering Himself, and the Spirit’s love applying the finished work to believers’ hearts. It is the triune God together who, in effect, says: “Humanity owes a debt they cannot pay – let Us pay it Ourselves.” Thus, the cross is God’s self-substitution for sinners.

We also saw that alternative atonement theories like Christus Victor, Moral Influence, and Ransom, while highlighting important biblical truths, do not negate PSA but rather build upon it or flow from it. Christ’s victory over Satan (Victor) was achieved by removing the legal claims against us (Col. 2:14-15), effectively disarming the accuser by canceling our sin-debt. The moral influence of the cross, the example of love is profound precisely because the cross accomplished something real, when we realize “He loved me and gave Himself for me,” it breaks and remakes our hearts. And the ransom paid was not a whimsical deal with the devil, but the very cost of our redemption demanded by God’s holy law, a ransom to God that Christ lovingly paid “He gave Himself as a ransom for all,” 1 Tim. 2:6.

In summary, PSA is the linchpin that holds these facets together, ensuring that our salvation is not merely a display of power or a persuasion of our minds, but a justice-satisfying, relationship-restoring, cosmos-renewing act of God.

PSA is not a novel theory but part of the “faith once for all delivered to the saints”.

Finally we addressed that in an age where some modern readers want to allegorize away uncomfortable concepts (like sacrifice, blood, and wrath), we can stand with the Fathers in affirming a literal reading: the sacrifices were real, they taught that “without blood there is no forgiveness,” and they pointed to the Lamb of God who indeed by the shedding of His blood obtained eternal redemption (Heb. 9:12).

In closing, PSA is a strong theological framework because it answers the problem of guilt and shame, I can know I’m forgiven not because God shrugged off my sin, but because Jesus took responsibility for it and dealt with it completely. It also gives a profound sense of God’s holiness, He hates sin so much that it required nothing less than the death of His Son to atone for it, which in turn makes me hate my sin and adore my Savior all the more. PSA leads to awe and grateful love: “Lord, you satisfied Your own justice to save me, how great You are!”

It is coherent, because it is firmly anchored in God’s consistent character revealed throughout Scripture both just and loving. It has stood the test of controversy, answering objections with careful nuance. And above all, it brings glory to God and humility and joy to us: “May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Gal. 6:14). At the cross, God’s justice blazed and God’s mercy embraced, and we stand forever safe in the shadow of that cross, singing the praises of the Lamb who was slain – “for by Your blood You ransomed people for God” (Rev. 5:9). Amen.

This was very insightful, and a great listen. One I could listen to over and over and think through something new each time. What a lot of research, time, and prayer must have gone into this!